2015 — 2017

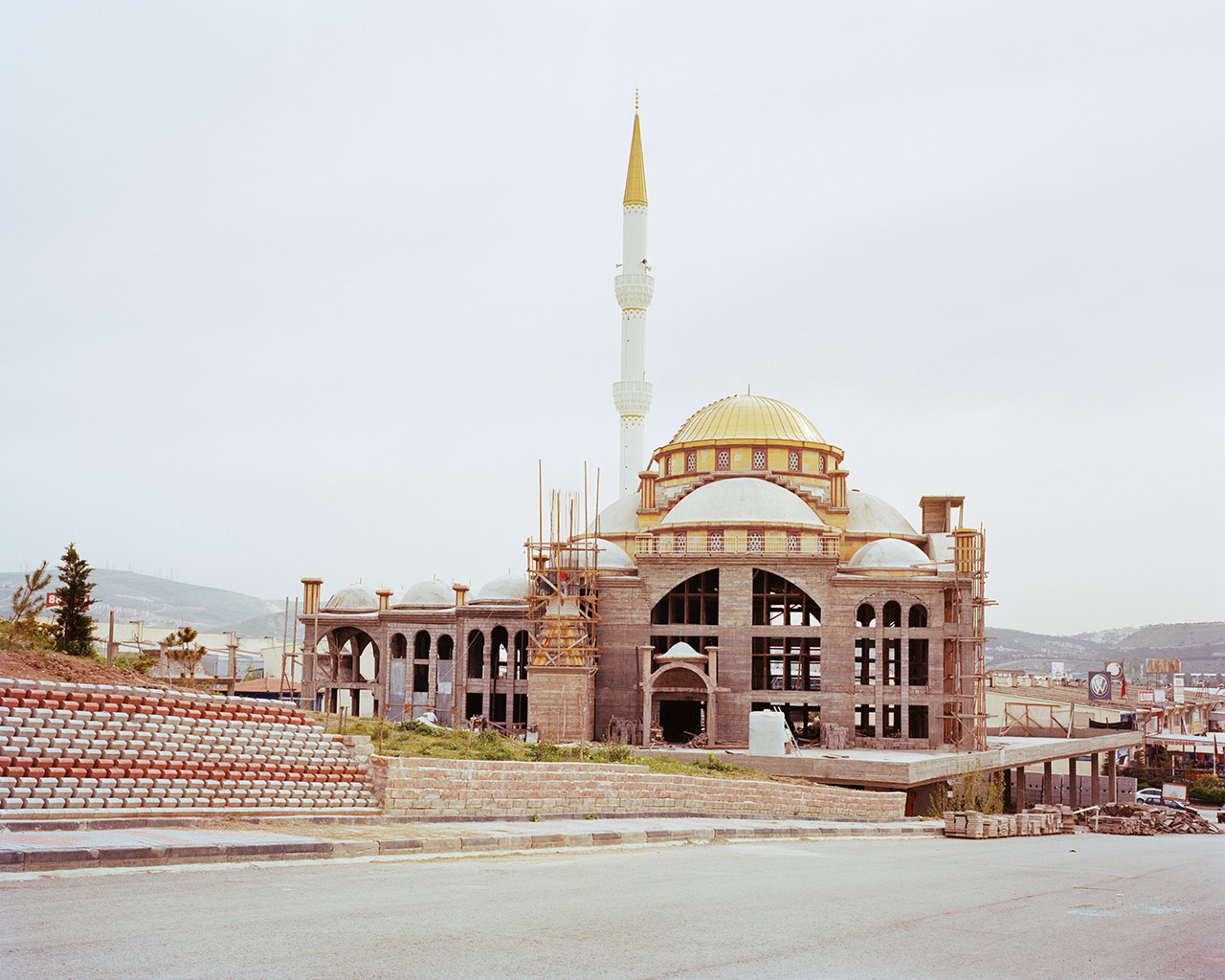

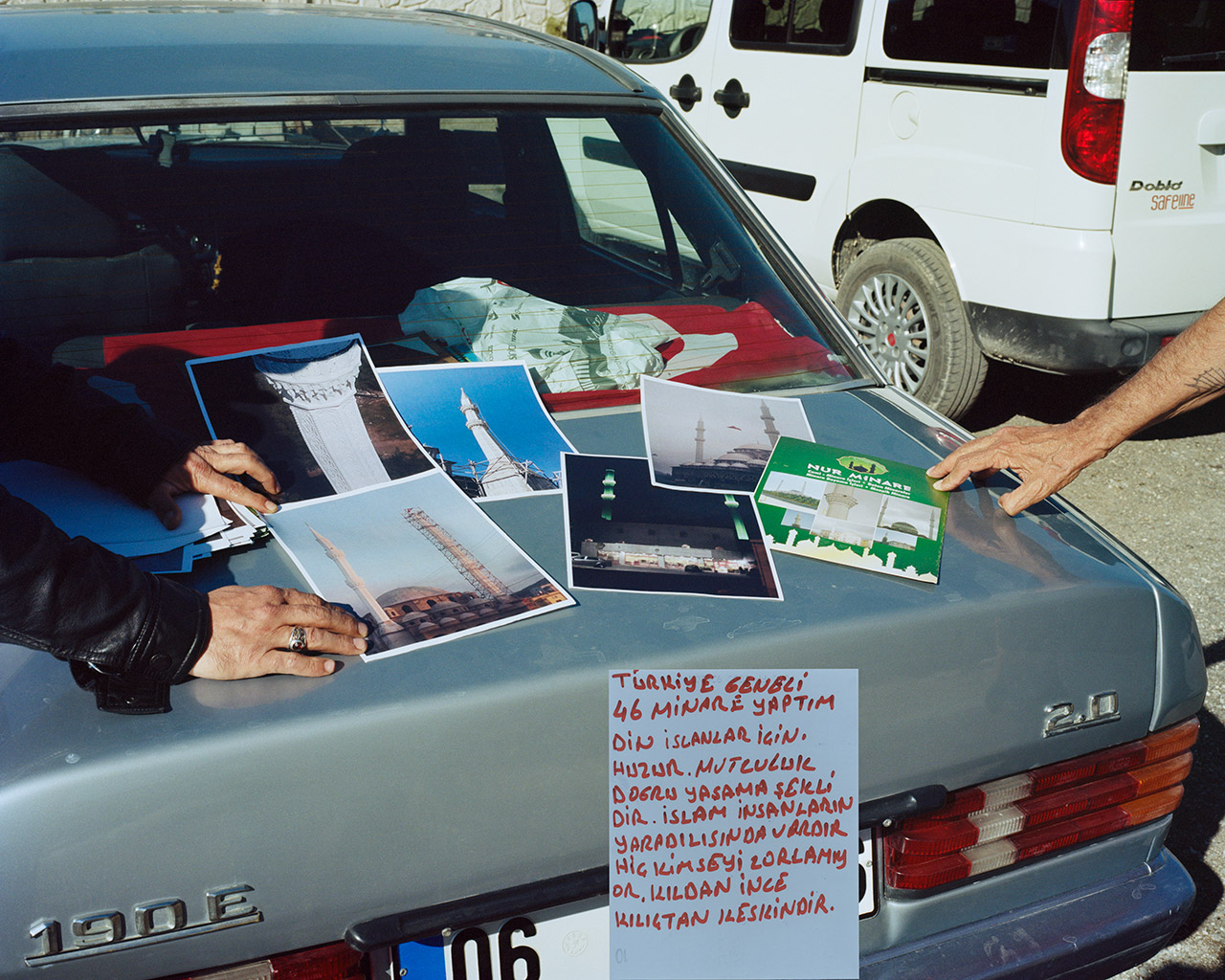

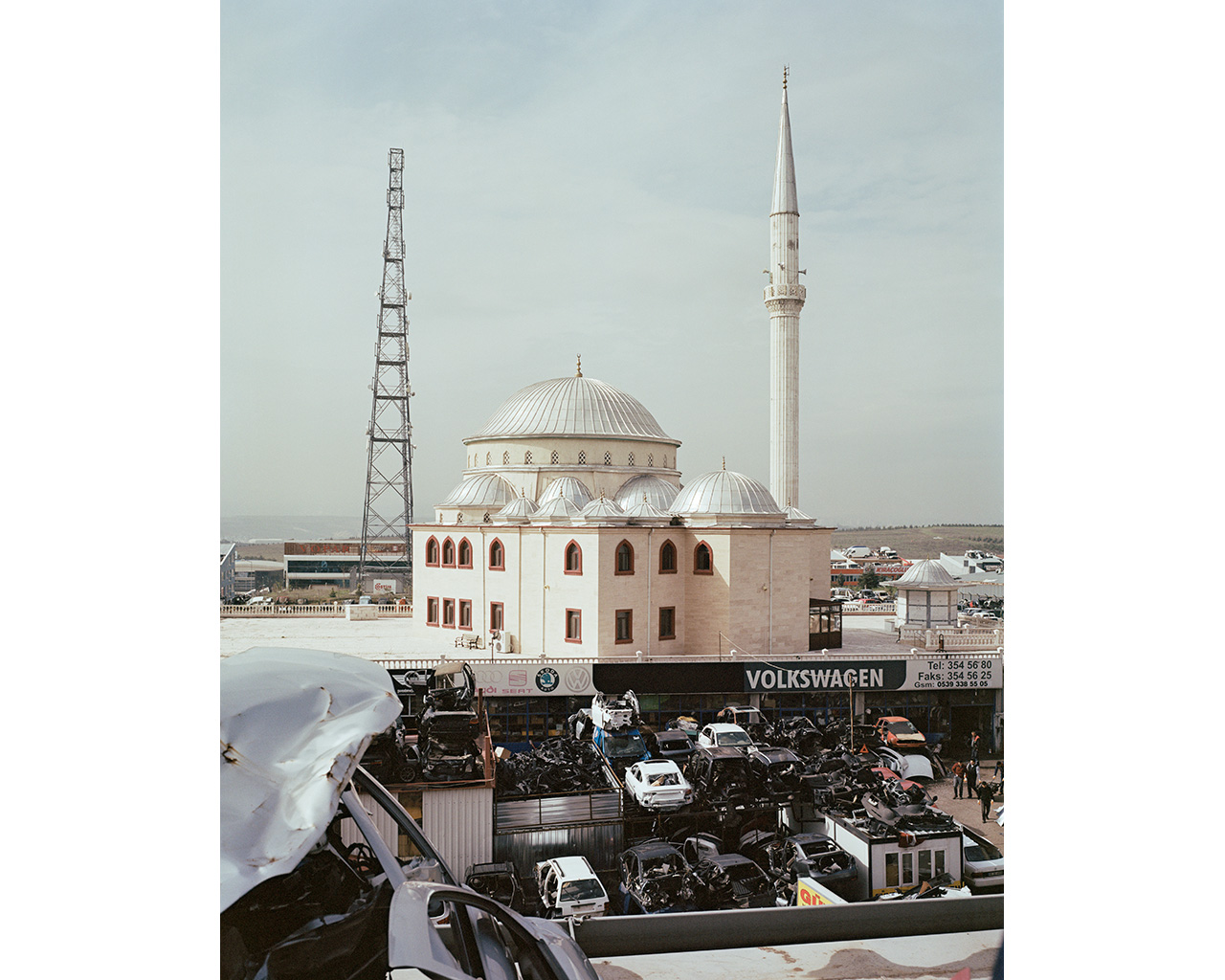

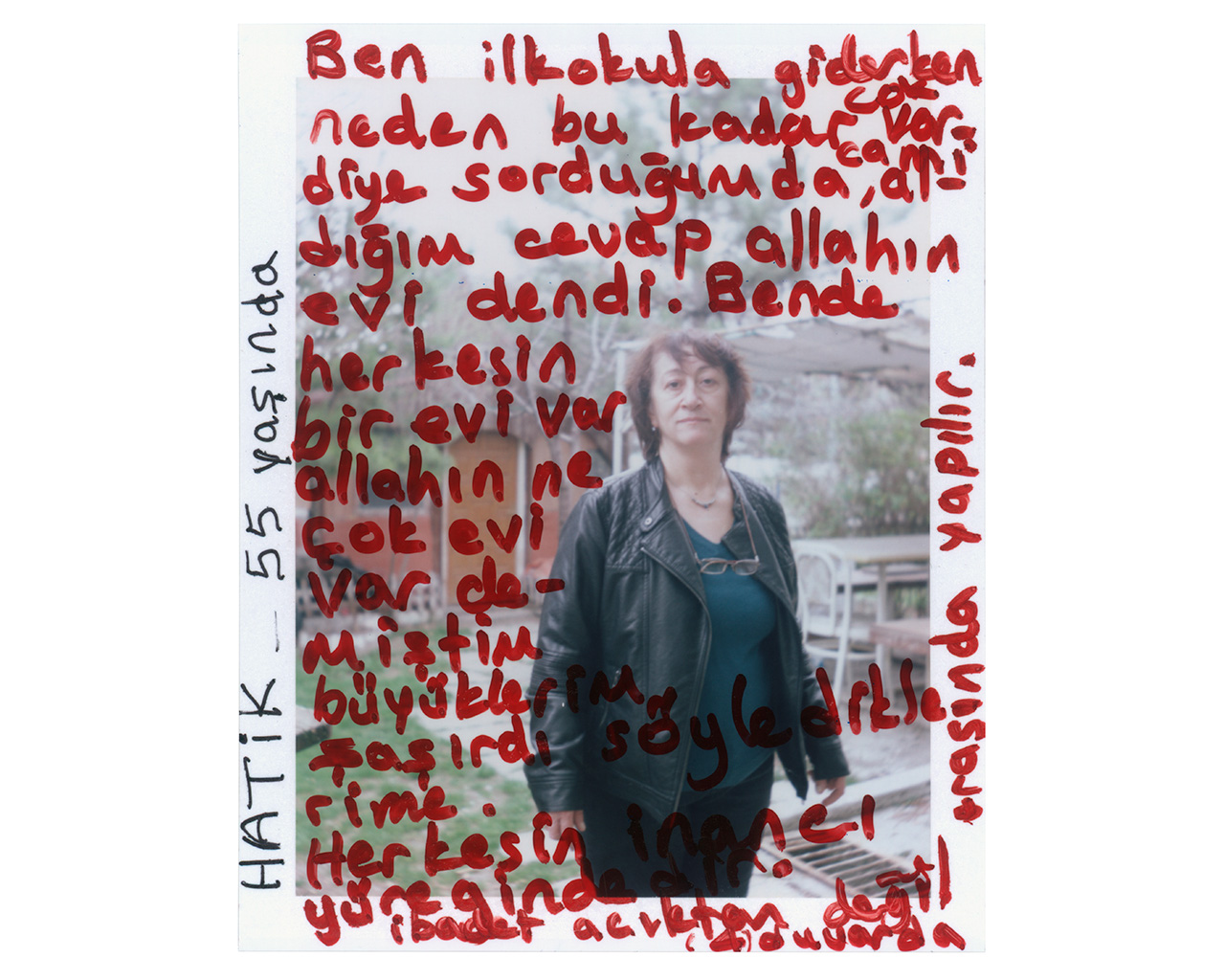

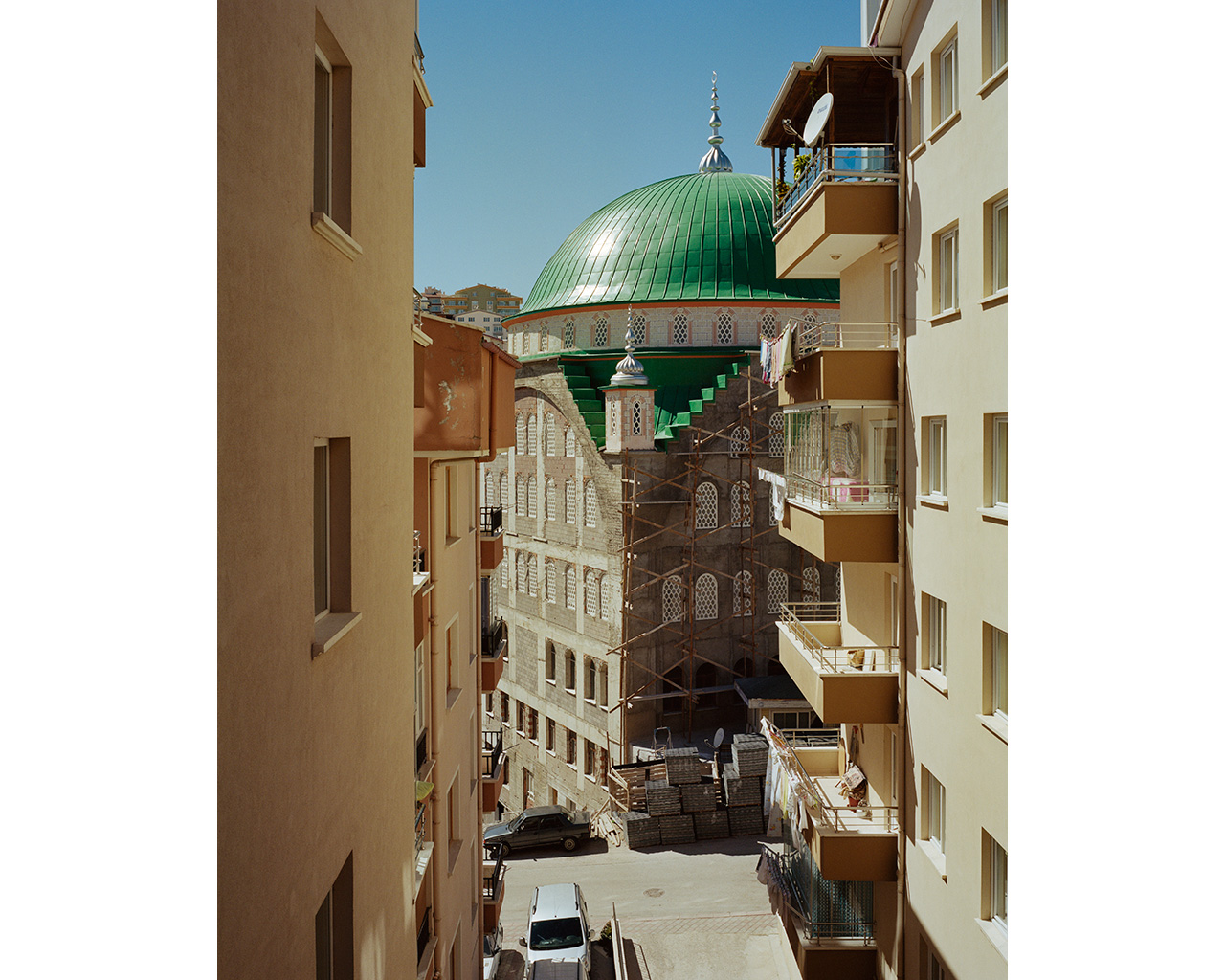

Brave New Turkey is a documentation of newly built and state sponsored mosques in a Neo-Ottoman-Style in the urban landscape of Ankara and Istanbul.

Many of Turkey’s 75,000 mosques were historically built and maintained by the Diyanet, according to a community’s needs for prayer space. It was not assumed that a new neighborhood or a college campus, for example, necessarily required a mosque. Such decisions depended on both the ruling government’s perspective on religion and society and the levels of urban and rural development at the time. Between 2006 and 2009 — Erdogan became prime minister in 2002 — 9,000 additional mosques went up throughout Turkey. Like his bridges, airports, pastel-pastiche apartment towers and luxury shopping malls, Erdogan’s mosques have themselves become engines of national economic growth, as well as symbols of his New Turkey.

(Suzy Hansen, ‘The Second Conquest’, NYT Magazine, June 18, 2017)

Returning Turkey to the glories and origins of its Ottoman past and ending Atatürk’s secular constitution has been one of the primary goals of Recep Erdoğan throughout his long rule of Turkey since 2003, first as prime minister and now as president with growing executive powers. Thanks to the country’s economic boom, between 2010 to 2017, which was driven by cheap capital following the global financial crisis, the AKP, Erdogan`s party, has improved healthcare, urban infrastructure and prosperity, but on the other hand has made control of religious affairs a priority.

The Diyanet, the Directorate for Religious Affairs fulfills this role and helps to legitimize the religious backswing of Turkey since 2010. Originally created by the Turkish state to exercise oversight over religious affairs, is now firmly under the control of President Erdoğan, and has turned into a supersized government bureaucracy for the promotion of Sunni Islam. It caters only to the Muslim population; but it

is indifferent to the diversity of Turkish Islam. There are about 15 million Alevis, perhaps three million Shi’a, and over a million Nusayris. And then, 12-15 million Kurds following the Shafi’i and not the Hanafi school.

Under the AKP, Diyanet has grown exponentially. In less than a decade, Diyanet`s budget has quadrupled to over $2 billion per year, and it employs over 120,000 people, making it one of Turkey’s largest institutions — bigger than the Ministry of Interior.

(Svante Cornell, ‘The Rise of Diyanet: the Politicization of Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs’, The Turkey Analyst, October 9th, 2015)

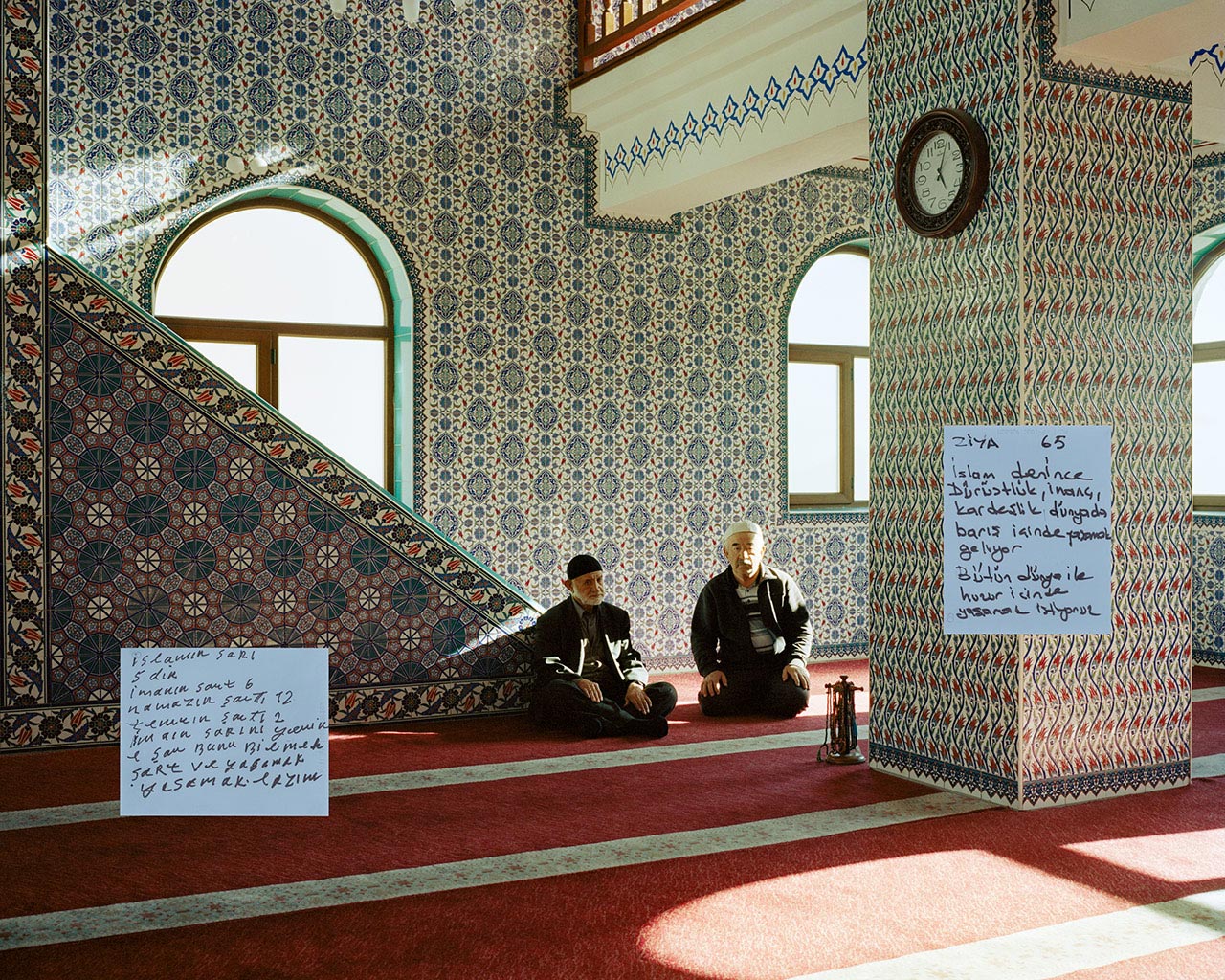

The Diyanet has become a political instrument for the government to reshape Turkey. It comments on political affairs, advises citizens on religiously acceptable conduct. It is also the main investor for thousands of the newly built mosques in Turkey and abroad. Most of them built in the imperial Ottoman style with their distinctive domes and minarets, following precisely the architectural tradition of Mimar Sinan (1490 - 1588) the master of classical Ottoman architecture. Given the influence that the Diyanet-controlled mosques have on the conservative masses across Turkey, this development is probably both among the most consequential, and among the most unknown, accomplishments of the AKP.

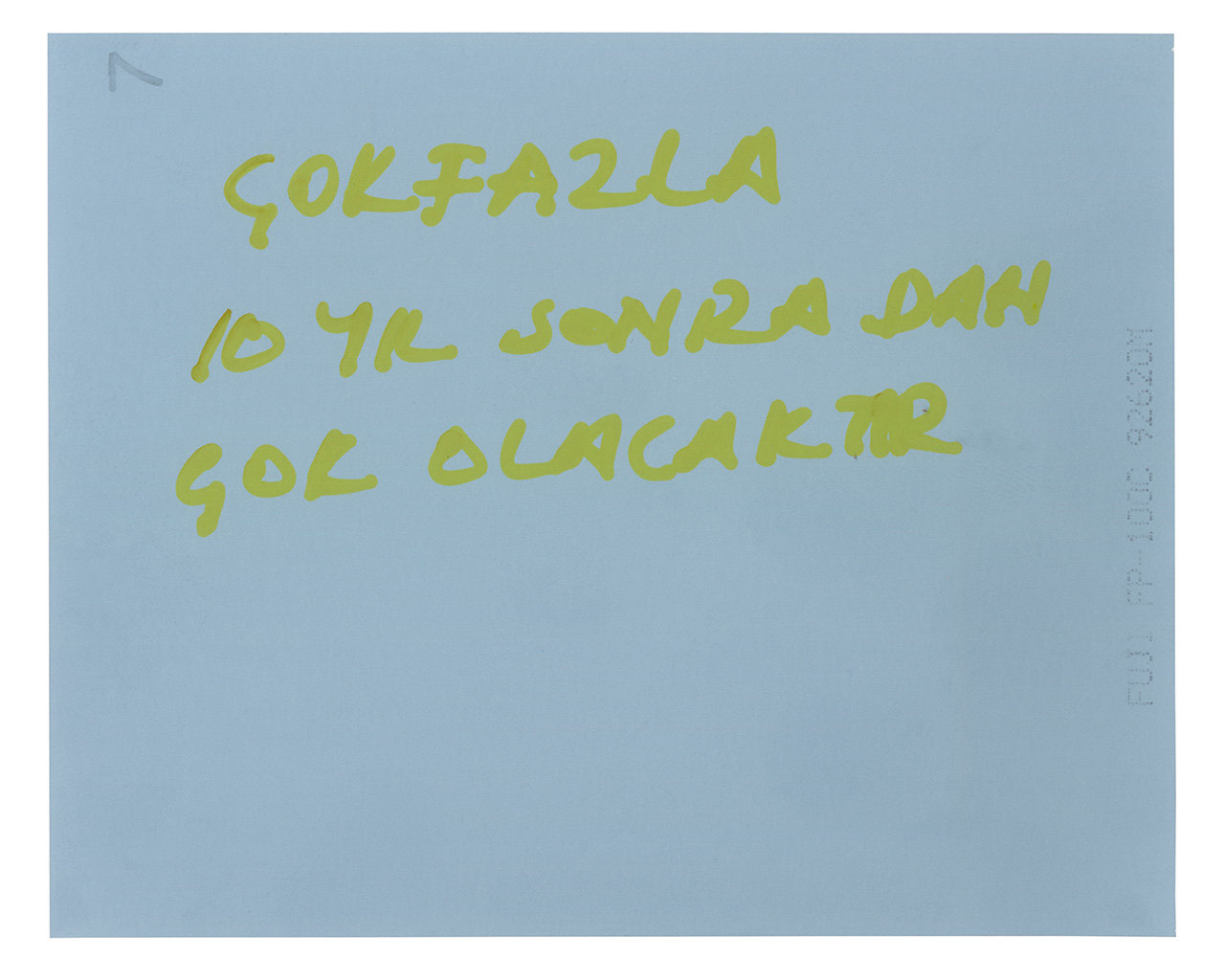

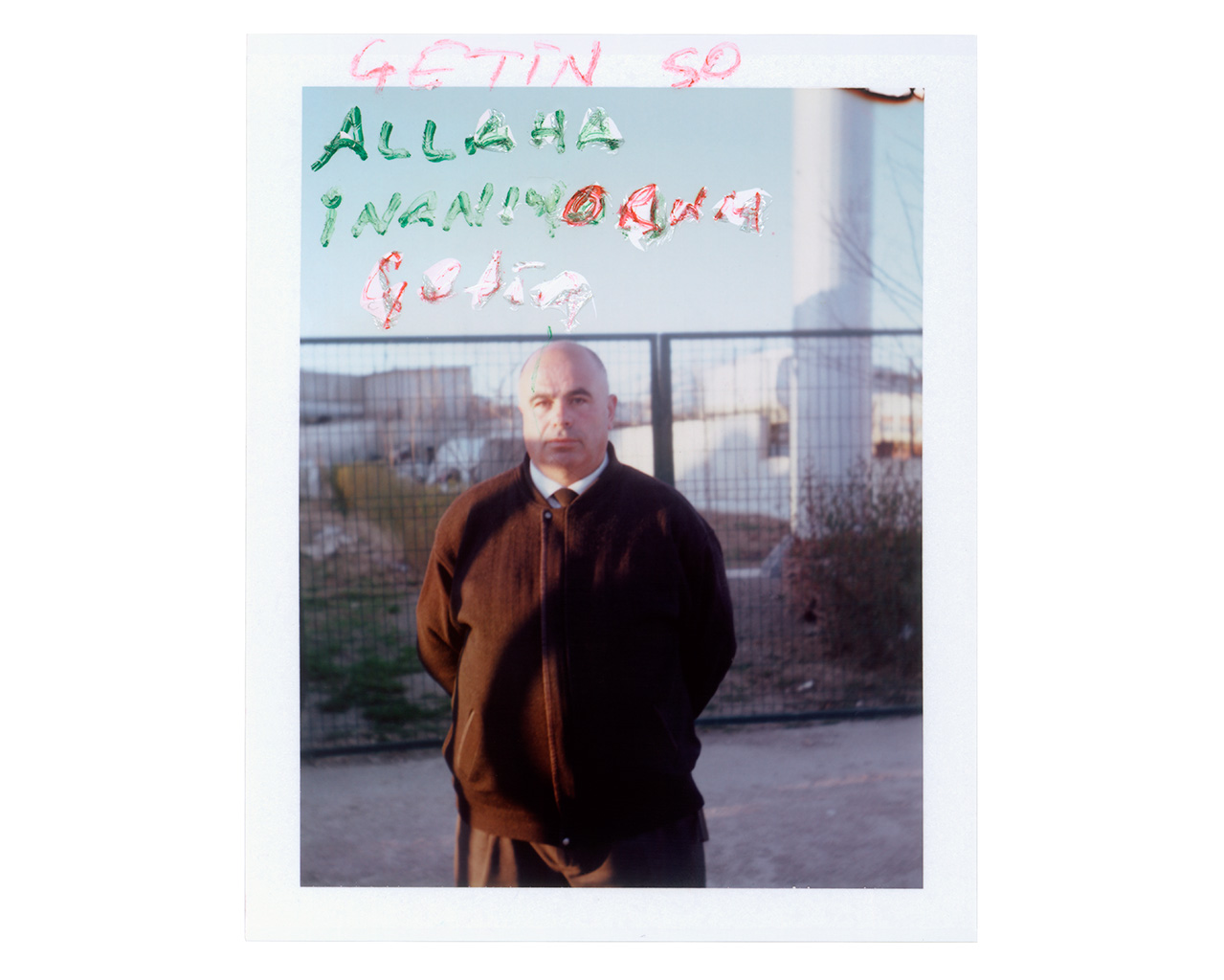

Brave New Turkey reflects this phenomenon as a symbol of change and power that reaches beyond national borders. It is less about architecture in a classical sense, but rather how architecture reflects power and how ideologies are manifested in it. It reflects a newly tied compound of religious and cultural identity, against the backdrop of a constant exclusion of minorities, a reckless fight against those whose convictions are different and an unresolved question of what is Turkish identity?

This is an excerpt from the work. Please get in touch for more information.